Digital platforms have vastly increased content reach, but this also amplifies the impact of harmful information.

Content moderation is a constantly changing field, adapting to political pressure, new regulations, and societal needs, all while aiming to protect users.

The effectiveness of current and new moderation techniques is being evaluated, but the fundamental need to safeguard users from harmful content remains constant.

July 15, 2025

Introduction

The digital transformation in the past decades has blurred the lines between the online and the “real” world, now both realities intertwine and affect each other. An example of this is the unfortunate event last July in Southport in the UK where three children were stabbed at a dance class. After this, posts on social media spread misinformation on the identity of the attacker, blaming it on a “Muslim asylum seeker who had arrived on a small boat”. Despite this not being confirmed by the police or other authoritative source, it inflamed sentiment and led to protests in various cities around the UK, including hateful demonstrations where mosques were attacked, businesses owned by people of color were targeted and cars and police vehicles were set on fire.

This is not the first time social media has been linked with protests, more examples of this are the Capitol riots in the United States in January 2021 and the ransacking of the Brazilian Congress in 2023.

It is important to note that social media is not the only component in inciting violence, other aspects play a role like socioeconomic wellbeing within a community, and political discourse. However, the capacity of social media to amplify reach, plays an important role. This blog analyzes how social media companies moderate online content, what they do to prevent harmful content from appearing, and how current geopolitics are affecting the way we understand content moderation.

What is Content Moderation?

Over 90% of internet users use at least one social media platform owned by a major tech player (Meta, Alphabet, X, Microsoft, Bytedance). To reduce or prevent the spread of harmful content in these platforms, content moderation flags, restricts, and often removes content that does not meet certain standards determined by the hosting platform. These standards reflect both company values and relevant legislation. In the UK, for example, content that incites violence is illegal under the Online Safety Act. Online services that operate in the UK must mitigate and take action against illegal content appearing on their platforms or run the risk of being prosecuted under criminal law.

Content moderation may at first seem like nothing more than a prudent, routine practice that allows online platforms to, at the very least, reliably abide by national and international law. In reality, content moderation practices have been criticised since they began; common critiques include claims that it limits free speech and concerns around the working conditions of content reviewers.

How is Content Moderation Carried Out?

Initially, content moderation served to ensure platform content adhered to internal policies, commonly known as community standards. This process has since evolved significantly, now functioning as a critical mechanism for compliance with online service regulations, such as the EU Digital Services Act (DSA) and the UK Online Safety Act (OSA).

It is important to make the distinction that the DSA does not require platforms to actively monitor content, but to provide a channel for users and trusted flaggers to report uncompliant content and to have mechanisms in place to review said reports. On the other hand, OSA does require platforms to actively monitor and prevent harmful content from appearing in its services.

Content moderation is performed by human moderators and/or automated systems, with the approach often depending on the platform’s maturity and, in some cases, the content category (e.g. adult content, spam or health). For example, Pinterest reported in 2024 that 80% of “Non-compliant products & services” content was identified and deactivated using automated systems, whereas “Hateful activities” content saw 0% automation. This difference corresponds to how accurate a system is at identifying these categories, as well as the stakes of taking down that content.

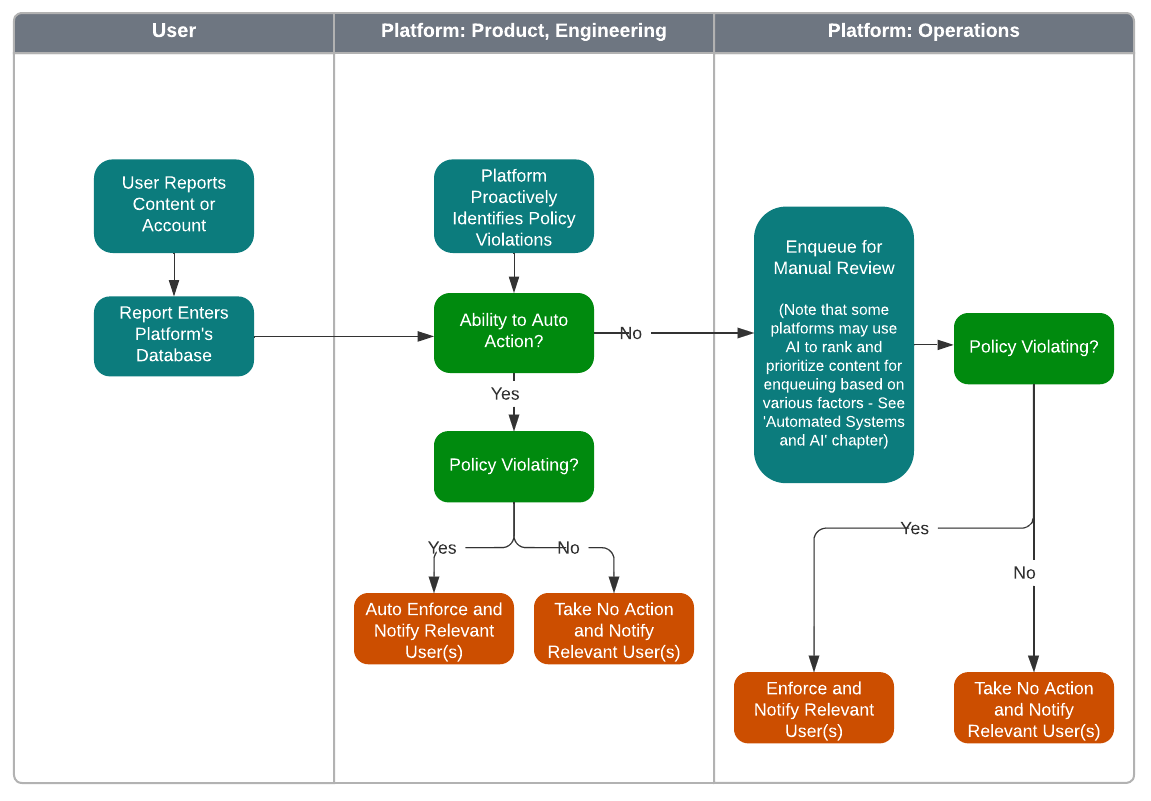

Presumed non-compliant content can be flagged through proactive monitoring or user reports. The content is then analyzed to determine policy violations; if a violation is found, the content is removed, and the user is notified. A comprehensive diagram from TSPA illustrating this process is provided to the right.

Furthermore, content moderation isn’t exclusively handled internally. Many platforms outsource aspects of this process to third parties, leveraging external expertise and increased capacity. A combination of internal and third-party moderation is often employed to capitalize on the strengths of both approaches.

Within third-party moderation, “trusted flaggers” offer specialized expertise in identifying online harm. As highlighted in the DSA, platforms should prioritize addressing reports from these entities.

However, this process is not without flaws. Criticisms include the unethical working conditions and mental health impacts on human content moderators who are mostly based in developing countries, as well as the potential biases of automated systems. As discussed in our previous blog [Read here], automated systems can be particularly inaccurate in languages other than English. A lack of contextual awareness also presents challenges, as evidenced by recent criticisms regarding the takedown of content related to Palestinian protests.

How Is Content Moderation Evolving

Motivations to change content moderation

Political shifts are a key driver behind the evolving landscape of content moderation on platforms. When announcing the changes to fact-checking programs in Meta, Mark Zuckerberg said he wants to oppose global censorship pressures, giving as example Europe’s increasing number of laws that institutionalize censorship, Latin America courts that order companies quiet take downs, and Chinese censorship.

In February, President Trump signed a memorandum pledging to defend American companies from what he termed “overseas extortion.” This referred to the repercussions of enforcing foreign laws, including potential fines or digital service taxes (e.g. DSA, OSA). The US administration also issued a memorandum stating it would cancel contracts with companies that “censor” their users.

The European Commission has rejected claims of censorship, stating that they do not force the removal of lawful content but only of harmful content. And that they do not prescribe the form that content moderation should take as long as it is effective.

These political actions, combined with platforms’ existing content moderation practices, have raised concerns among digital rights defenders, trust and safety professionals, and other stakeholders. They fear that protections on platforms will diminish, potentially leading to an increase in harmful content and leaving users and advocates without effective mechanisms to remove it.

Platform moderation

Approaches to Content Moderation will vary depending on the platform. For large platforms like X and the Meta suite, there has been a recent trend away from manual forms of Content Moderation to automated review systems and crowdsourced moderation in the form of Community Notes.

X

X performs Content Moderation with a combination of human oversight and automated content review technology. In the company’s Transparency Report, published in October 2024 to comply with the EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA), X states it couples this review process with “a robust appeals system” that allows users to quickly flag content for review. Flagged content might be routed to one of the over 1200 people X employees in Content Moderation roles.

In 2023, X began a large-scale rollout of their Community Notes feature. Community Notes function as crowdsourced Content Moderation for user-generated content; Community Notes appear against a post on X if the company’s ‘bridging’ algorithm identifies that enough users from varied perspectives find the Note to be useful. X assesses the point of varied perspectives by measuring how likely users are to agree with each other; if users unlikely to agree with each other (based on previous Community Notes ratings) unilaterally rate a Community Note as being helpful, that Community Note is determined to be useful to people of different perspectives and is published. X employees cannot modify or remove Community Notes unless they are found to violate the company’s Terms of Service.

Meta

In 2016, Meta began performing Content Moderation by contracting independent organisations to fact check content on Facebook and Instagram. These organisations are based around the world and employed thousands of reviewers who viewed and evaluated content manually.

In 2025, Meta announced it would end its third-party fact checking contracts in favour of a Community Notes model similar to that being used on X. Like those on X, Community Notes in Meta’s products will not be written or moderated by Meta employees and will be published based on whether users “with a range of perspectives” agree on a Note. In tandem with the Community Notes rollout, Meta is also scaling back automated moderation for all content except that which is illegal or high-risk. For content that is “less severe”, Meta will only review and take action after the content is reported by users. Zuckerberg said he will make sure the new model complies with its obligations in the EU and UK before rolling out the model.

Meta also made a series of changes to its Community Guidelines, which sets looser restrictions and allows for more hate speech, misogyny, racism, and anti-LGBTQ content. Including the widely criticised allowance of allegations that gay or transgender people have a mental illness.

Consequences of content moderation changes

Currently, X is being investigated by the European Commission on its compliance with the DSA. Among other areas, the investigation is around its obligations to mitigate the risk of spreading illegal content and to help users flag content, measures against misinformation (effectiveness of Community Notes), and the deceptiveness of bought blue check marks. In a preliminary finding, the Commission found that the blue checks misled users into thinking the content was trustworthy, when it wasn’t always the case. The commission is still investigating the compliance with the other obligations, and the fines can go up to 6% of yearly worldwide revenue or agree on remedies to avoid fines. Some think that the Commission hasn’t fined X or released official findings because of Musk’s previous close ties with the US administration.

The consequences that these changes to content moderation will have are still to be determined. However, many users have reported that they trust information they see in X less than before.

Challenges Ahead

Misinformation

Crowdsourced Content Moderation approaches like Community Notes often take more time to be implemented as they require a large number of users to interact with and reach a consensus on a post. This consensus must also be identified by the ‘bridging’ style algorithm put in place by the platform, a calculation that can be slow to execute. One study found that Community Notes can take between 7 to 70 hours to appear on posts sharing misinformation. This means that a post containing misinformation will spread unrestricted and could even go viral until users reach a consensus on the post that the platform’s algorithm also recognises and publishes as a Note.

Even if consensus is reached and implemented through a Community Note, this consensus is not necessarily truthful. Without independent factchecking or consistent guidelines, the Community Notes model may amplify content that many users with varied perspectives find “interesting and compelling” but that is not accurate. The broader social risks implicit in the spread of inaccurate information cannot be overstated; as The Conversation reports, “unchecked misinformation can polarise communities, create distrust, and distort public debate.”

Harmful content

One of the goals of Content Moderation is to prevent harmful content from spreading widely on a social media platform. Some of the most heavily moderated forms of harmful content are those that represent graphic violence, incite hate, or pose a danger to children.

The traditional approach to Content Moderation, where humans manually review content, has been heavily criticised for how it affects the health and wellbeing of moderators who view and assess distressing, violent, or illegal content daily. In 2020, Meta agreed to pay a settlement of $52m in a lawsuit filed by former moderators against the company. The former moderators, some of whom were diagnosed with PTSD as a result of the content they had to review, argued that Meta “failed to protect workers…from the grave mental health impacts of the job”.

Moving away from manual content review systems also poses risks; an automated and/or Community Notes model may result in more harmful content being shown to the people using social media platforms. Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg admits that the tradeoff to the new Community Notes system is that the company will “catch less bad stuff” while prioritising a process that leads to fewer posts being “accidentally” or wrongly removed. It is unclear if or how this reactive approach to Content Moderation will be able to abide by international law, like EU’s Digital Services Act and the UK’s Online Safety Act, that defines and protects against specific forms of harmful and illegal content.

Content fragmentation

The founding fathers of the internet imagined it would be a globally connected network with information freely and easily accessible and sharable from different networks. The current landscape where there are different determinations of what should be online puts this idealized globally accessible information under threat. To illustrate, the changes to Meta’s content moderation are only in force in the United States, while they ensure they can be rolled out in jurisdictions with stricter online services regulations. Some information that would not be accessible in Europe, might be accessible in the US and vice versa. This risks the creation of echo chambers, sectioning information to a geographical area of users, reinforcing same ideas and risking to limit universal access to information.

Conclusion

Digital platforms have revolutionized the way content can be distributed, expanding the number of people that can see and interact with information. This expansion also exacerbates the effects harmful content can have. Content moderation is an ever-evolving field that aims to safeguard users against harmful content. In these times, we are seeing more changes in the way content is moderated, a consequence of political pressure, regulatory developments and societal demands. The future of content moderation is still being decided and the effectiveness of old and new techniques is being tested. One aspect stands true, content moderation is needed to safeguard users from harmful or disturbing content.

Sources:

- https://transparency.x.com/dsa-transparency-report.html

- https://transparency.meta.com/en-gb/enforcement/detecting-violations/how-review-teams-work/

- https://about.fb.com/news/2025/01/meta-more-speech-fewer-mistakes/

- https://help.x.com/en/rules-and-policies/enforcement-options

- https://help.x.com/en/using-x/community-notes

- https://ico.org.uk/media/for-organisations/uk-gdpr-guidance-and-resources/online-safety-and-data-protection/content-moderation-and-data-protection-0-0.pdf

- https://ico.org.uk/about-the-ico/media-centre/news-and-blogs/2024/02/information-commissioner-s-office-tells-platforms-to-respect-information-rights-when-moderating-online-content/

- https://www.ofcom.org.uk/siteassets/resources/documents/research-and-data/online-research/online-harms/2023/content-moderation-report.pdf?v=330128

- https://techcrunch.com/2023/08/02/x-formerly-twitter-streamlines-its-crowdsourced-fact-checking-system-community-notes/

The Authors

Cristina Herrera is a Senior Analyst at Adapt where she works on human rights, engagement with international organizations, regulation tracking and analysis and consumer trust & safety. She holds an LLB from the Autonomous University of Queretaro, a masters in Economics from UNAM and an LLM in Innovation, Technology and Law from the University of Edinburgh.

Maria Samper is a London-based professional in technology, consulting, and research. She graduated from the London School of Economics with an MSc in Media and Communications, and is now working in market research with a focus on how new technologies are affecting global labor trends. Her main interests are emerging technology policy, AI governance, and sustainable digital infrastructure.